Major League Baseball is working to determine just how the 2020 season, abbreviated by the COVID-19 epidemic, will be scheduled and when it will begin. Already the loss of games in March, April, May (and likely part of June), has created a need for alternative baseball media content.

Much of the fill-in media has focused on how the season might be restructured and what the impact of seventy or eighty lost games will be for players, for MLB franchises, and for the future of the game itself.

Much of the fill-in media has focused on how the season might be restructured and what the impact of seventy or eighty lost games will be for players, for MLB franchises, and for the future of the game itself.

For me, it’s instructive to look back to the last era in which MLB seasons were cut short, baseball games were cancelled, and owner revenues and player salaries evaporated.

That would be from 1972 through 1995, when relentless labor strife between the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) and Major League Baseball owners created a 24-year period during which there were eight players strikes or owners’ lockouts.

Which means fully a third of those twenty-four MLB seasons were negatively impacted, creating the worst era in the history of the game in terms of disruptions, loss of games played, a cancelled World Series, and loss of significant revenue for both sides.

The other two thirds of of those 24 seasons were not exactly a happy time. In between the strikes and lockouts the relationship between MLB management and labor seethed with rancor, mistrust, and vitriol.

How did this labor war era between the players’ union and baseball owners happen and why was it allowed to happen?

The MLB Labor Wars Part 1: A Small Ask Begins the Nightmare

In 1953 professional baseball players from both the National and American Leagues formed the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA)—the players’ union. And then began the fight for recognition from baseball owners. It wasn’t until 1966 that the union was officially recognized by MLB.

Miller would have that job for the next seventeen years and the professional sports labor revolution he created and won would eventually earn him a place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The economic structure of professional baseball was about to be turned upside down and players’ rights would finally be brought to the bargaining table and legitimized.

1972 Season – The Players Take a Walk

This was the first time in baseball history the players went on strike. (There had been a one-day work stoppage staged on May 18, 1912 by Detroit Tigers players because the team’s star player Ty Cobb had been suspended for charging into the left field stands several days earlier to assault a disabled fan who was taunting him.)

MLBPA Executive Director Marvin Miller called the 1972 strike after the union requested to have MLB increase the players’ pension fund contributions to account for inflation and cost of living expenses. It was a reasonable, relatively small ask. But the owners mistakenly saw the request as a golden opportunity to break the recently recognized union’s back and reassert MLB’s stranglehold on all the game’s economic strings.

The missed games were not made up because MLB owners refused to pay players for the time they were on strike. As a result, the 1972 season was shortened to 153 games.

1973 Season – The Revenge of the Rich White Guys

For the first time in baseball history the owners locked the players out of Spring Training, from February 8 to February 25, 1973.

The issue here was a new Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) and salary arbitration—the MLBPA wanted a neutral arbitrator to decide arbitration-eligible player salaries. The arbitrator would choose between the player’s request and the owners’ offer and their decision would be final.

Baseball owners would not give anyone, the MLBPA or an independent arbitrator, the power to decide how their money was spent.

So the owners and their attorneys decided to get cute after their stinging defeat the previous season. With a preemptive Spring Training lockout they figured to slam the brakes on the union’s momentum but not lose revenue by missing any regular season games.

But the MLBPA happily kept its membership away and once again the owners blinked and a new three-year CBA was signed between both parties that included the players’ arbitration demands.

1976 Season – Owners Sing the Reserve Clause Blues

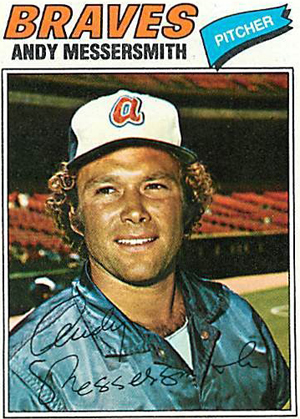

The recalcitrant owners again locked the players out of Spring Training. They were angry that in December 1975 an independent arbitrator ruled for the players’ union over the “reserve clause” that kept baseball players tied to their teams even after their current contracts had expired.

After 17 days of huffing and puffing, Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn ordered Spring Training to resume and negotiations continued on a new agreement.

On August 19th the new agreement was reached which included giving players the right to become free agents after six years of service time. The regular season was not affected.

1980 Season – The Players’ Union Goes 4 for 4

The players went on strike by walking out on the final eight days of Spring Training because a new CBA was being held up by the owners over free agency compensation.

The MLBPA also notified MLB that the players would start the season but then go on strike on May 23rd if the basic agreement wasn’t signed and in place. An agreement was reached on the morning of May 23rd, with both sides agreeing to a new CBA and the creation of a joint players-owners committee to work on free agency questions.

1981 Season – Tell it Goodbye: Hundreds of Games, Millions of Dollars

The unfinished mess of the 1980 free agency strike spilled into the new season with a vengeance and resulted in the second in-season players strike in the game’s history.

The MLBPA was determined to continue its winning streak and dug in on the main hold-up surrounding the free agency issue, specifically that a team signing a free agent had to compensate the player’s former team.

For the owners, this was a final line in the sand and they were ready to stare the union down. MLB owners now had a $50 million strike insurance policy they could draw from and they were prepared for a fight. And things happened fast.

In early February, the joint players-owners free agency committee disbanded, unable to resolve the free agent compensation issue. On February 19th, the owners unilaterally imposed their free agent plan: any team signing a free agent had to give up a roster player and a draft pick to the player’s former team.

On February 25th, the MLBPA approved a players’ strike set for May 29th. The day before the strike, both sides agreed to hold off and let the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ask a Federal judge to rule on the compensation issue.

As players missed paychecks and the owners started collecting on their strike insurance, for the first time in the 20th century there was no baseball played on July 4th and the July 14th All Star Game was cancelled.

In a flurry of negotiations and meetings, which would eventually include Secretary of Labor Raymond J. Donovan, a marathon 12-hour session on July 30th created a settlement agreed to by both sides. The All-Star Game was hastily rescheduled in Cleveland for August 9th and the rest of the regular season began on August 10th.

A total of 713 games were cancelled by the strike and it’s estimated that almost $150 million in revenue was lost. Players lost somewhere around $4 million in salaries. For the only time in MLB history, playoff teams were decided by “first half” and “second half” division winners.

1985 Season – The Stakes Are Now Measured in $Billions

The players staged a two-day midseason strike August 6th & 7th, cancelling 25 games.

In 1983 MLB signed a whopping $1.125 billion six-year TV deal with NBC and ABC. The players’ union demanded a commensurate piece of that deal with an adjustment on player pensions and no cap on salary arbitration.

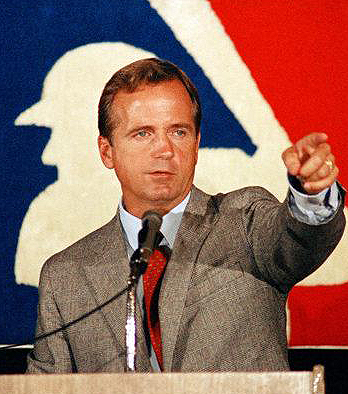

Ueberroth would later make up for that gaffe by enabling the owners to illegally collude on free agent signings from 1985 to 1987, costing dozens of players millions of salary dollars.

As part of the settlement, the owners also agreed to contribute $33 million to the players’ pension fund in each of the next three years, and $39 million in 1989. The minimum player salary also went from $40,000/yr to $60,000/yr. The 25 games missed during the two-day strike were made up at the end of the season.

Amazingly, MLB owners were still convinced they could stop the players’ union and somehow turn back the clock.

Next–

The MLB Labor Wars Part 2: Prelude to Labor-Armageddon

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!